Top leaders in Latin American countries have started, expanded and sustained highly profitable and impactful businesses despite the adversities of their ever-changing and unpredictable social, political and economic context. As the rest of the world is immersed into the prevalent VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous)1 environment after the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, we believe there are some lessons that can be learned from Latam leaders coping with challenging environments well before this pandemic began.

This health crisis has shaken the stability and foundations upon which most companies and leaders make decisions and solve problems in developed economies. Thus, the existing structures and models of organizational behavior cannot be taken for granted anymore. This has turned the spotlight in the direction of those who are used to seeing the world through a less predictable and well-functioning environment.

Today’s senior leaders started their careers in Latin American countries three decades ago, when many of the region’s countries were expanding their participation in the free market. As a result of the opening of Latin American markets, massive investments were made, taking advantage of the region’s significant natural resources (e.g., corn, soybeans, gold, copper, oil) as well as its huge young workforce gradually becoming a large consumer population and strategic locations (e.g., proximity to USA and commercial routes opened by the Panama Canal).

These leaders were presented with the opportunity of joining global corporations, where they forged successful corporate careers. However, they developed their expertise in countries where political instability, weak rule of law, insecurity and social unrest have always been present. As such, these leaders have navigated in a chaotic context, characterized by economic booms, regulatory uncertainty, deficient access to justice and social instability. These contextual factors have provided leaders with particular inputs (challenges, opportunities and barriers) that have shaped their mindsets and behaviors to effectively solve complex business problems.

According to past sociological and social psychology studies, Latin American leaders differ from their equals in other regions in a number of characteristics. The premise underpinning these studies

is that culture matters in how leaders emerge and are selected, developed and seen.2 Yet we tend to classify leaders under universal leadership frameworks mainly based on the Western European and North American populations and paradigms. This study assumes we need to better understand the nuances of our leadership framework in the Latin American region to leverage it in other regions that today face similar characteristics more often.

In our work as consultants, we are committed to helping individuals and organizations become more effective. This research into the predominant leadership styles of top executives in Latin America provides valuable insights about leading in crisis not just for leaders born and raised in the region, but also for anyone leading in adverse and uncertain environments.

Companies play a strong social role, it must be understood that it is not only about what you give to shareholders, but to communities and the environment.

Industrial Company CEO

Leadership styles through our culture framework

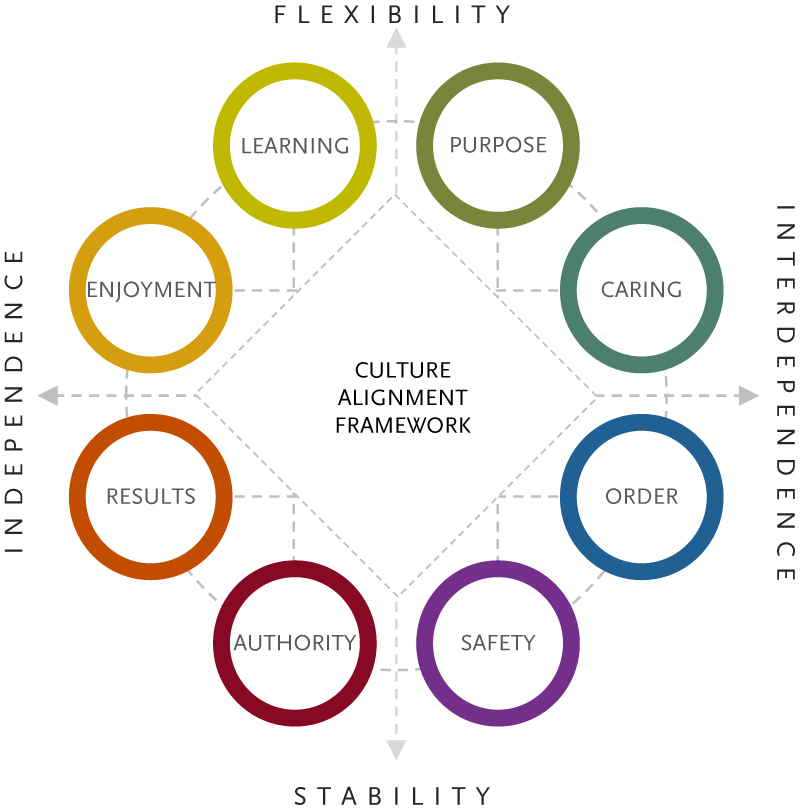

At Spencer Stuart, we believe leaders’ mindsets, attitudes and behaviors are underpinned by the dimensions of our Culture Framework (see FIGURE 1). This model is also used to describe individual preferences along the same lines as culture. The Individual Style Profile describes how executives act to resolve tensions around people and change through eight socio-cultural dimensions. Each style represents a valid and unique way to solve problems, view the world and be successful in an organization. Individuals’ top three styles reflect their main approach to leading an organization and its people.

In this study, we want to understand which styles in our framework are most predominant in Latin American leaders and how they look in Latin American leaders. We first reviewed existing literature on the topic to emphasize the underlying characteristics of individual executives in the region, especially as distinguished from leaders in other regions, mainly North America and Europe.

Figure 1. Spencer Stuart Culture Framework

Figure 2. Mapping past studies’ findings to Spencer Stuart's Culture & Individual

Style Framework

| Past research |

Spencer Stuart-ISP |

Made in LATAM findings |

| Value-Based |

Purpose |

Supported |

Paternalistic

Autocratic

Directive

Decisive |

Authority |

Supported |

|

Charismatic

Engaging/likable

Team-oriented

Interpersonal

relationships

Collaborative

|

Caring |

Supported |

| Ambitious |

Results |

Not supported |

| |

Learning |

Added trait |

Our mapping of findings from other studies to our model identified four styles as more significantly present in Latin American leaders (see FIGURE 2). First, most studies point toward a Caring style, which emphasizes being warm, sincere and relational. In general, the Latin America cluster’s culture is highly group- and family-oriented. Leaders in the region are described as charismatic,3 engaging/likable,4 team-oriented,5 collaborative6 and oriented to relationships7 (interpersonal). Generally, society disapproves of leaders who act alone and autonomously, and leaders are expected to develop social bonds with employees.8

The second style of our model that is aligned to empirical evidence is the Authority style. It emphasizes being bold, assertive and decisive. Traits that authors identify under this dimension are being paternalistic,9 autocratic,10 directive11 and decisive.12 They explain that leaders’ decisiveness is oriented toward becoming part of the group while retaining the responsibility for its outcomes.

In third place, past research has pointed to traits characteristic of our Purpose style, which emphasizes being high-minded, taking a long-term perspective and working toward the good of all humankind. This is what researchers call a value-based13 trait. Some have explained that this is about the expectations of leaders as contributors to a community’s social development.

Finally, evidence has additionally highlighted a fourth salient style, namely Results style,14 which is characterized by a drive to achieve and a focus on goals.

There is significant evidence to support the fact that all four of these dimensions of Spencer Stuart’s Culture and Individual Style Profile model are characteristic of Latin American leaders. In this study, we aim to further explain the dominant styles that define the mindsets and behaviors of world-class CEOs and C-suite leaders in Latin America. In addition to that, we explore how these styles take form in what we have defined as turbulent contexts.

How Latin American leaders lead

Data analysis revealed Latin American leaders manage people and solve problems drawing on five strengths: sense of community, humility, caring relationships and communications, crisis as opportunity and self-confidence.

1. Sense of Community

Leaders are passionate about the region. They are convinced that the growth potential for businesses and markets is wide open. At the same time, they recognize the existing social, political and economic flaws that prevail in most Latin American societies. Having worked in global companies, they benchmark their organizations’ context to their peers in developed economies. Fully aware of their reality, they have developed a personal purpose with a clear sense of community. They feel accountable for and are committed to the collateral social side of their circle of influence.

They have a genuine drive to make social impact through their everyday life work. They know that the formal jobs held by numerous members of the workforce who are performing operative, manufacturing and client service roles represent an opportunity for social mobility. Their employment has an impact on the wider community in which they operate and where they live. They are committed not only to achieving the business outcomes but also to fostering a sustainable environment for their communities.

Having acknowledged the limits of government leadership, they recognize the importance of contributing to the well-being of their society. They view the CEO role as an enabler to impact other people's lives. At the same time, they have a sense of loyalty and gratitude to their countries. They recognize the privilege attached to the opportunities given to them in order to succeed personally and professionally.

As leaders, they feel accountable for their own actions and decisions above and beyond their organizations. Besides the “financial value,” they see the “social value” in how and what they do as leaders. They are convinced that organizations can make a difference in the world they live in through the development of people and talent. Under this vision, some take further steps to link their strategies with social responsibility initiatives.

During the first months of confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic, these leaders attempted to keep operations going, motivated not only by their businesses’ financial performance but also to inject money into their countries. Aware of the economic fragility of their region, Latam leaders decided to focus on providing continuity to operations as the main priority after people's health.

Aligned to the Purpose style in our model, they are deliberate in behaving according to their personal purpose and take a longer-term view of the positive social impact they want to make for the people who work for their companies, their families and the communities that surround them. This legacy is linked to their recognition of the governmental void, which they know they can help fill through their actions. In turn, they can engage and motivate people not only through clear targets but also with inspiration.

2. Humility

The leaders we interviewed like to work and lead with values in mind. As individuals, their behaviors and decision-making processes are underpinned and guided by a strong and well-identified set of moral principles. As in many other cultures, transparency, honesty, integrity, trust and respect were commonly mentioned as part of their work ethic toolbox. However, the most distinctive value that our analysis identified is humility. Interviewees not only were vocal about the relevance of being humble, but they also presented themselves as modest, respectful and approachable during interviews.

In a region where inequalities and vertical structures of power prevail, showing humility is noticed by subordinates, especially at the manufacturing and operating levels. Leaders embrace humility not just as a strategy, but as a way of establishing long-term relationships throughout the entire organization, not just at the managerial level. Their teams appreciate this approach, since it breaks with the top-down approach that prevails in Latin American societies, where a people in a position of power can mistreat and look down on others.

l level. Their teams appreciate this approach, since it breaks with the top-down approach that prevail in Latin American societies, where a people in a position of power can mistreat and look down on others.

Humility was one of my first learnings as a leader, first listen. We are as important as other people are.

Healthcare Company CEO

It is common to see in these societies that government officials and politicians often make personal profit of their positions of power and public resources, despite the negative impact on the larger majority of underprivileged citizens. That is why for Latin American leaders interviewed in this study, proximity and being approachable and humble toward the workforce are highly valued assets for gaining trust and traction when they need to bring people on board.

Leaders maintain a down-to-earth attitude by constantly connecting throughout the different levels of the organization. This portrays leaders as approachable, sensitive and human as they present themselves as equals to the rest of the people, regardless of their status and hierarchical roles. A CEO from a consumer goods organization reported how he met with a sales representative of his company and he greeted her by introducing himself as someone who worked in the same organization as her. The sales representative recognized him and asked for a selfie with him that she then posted in the organization's network. However, the CEO reported that this is not always the case — sometimes he is not spotted, and he does not care about it. What he does is a genuine gesture of connecting regardless of his position.

This attitude is complemented by their values and the mindset of “always doing the right thing, regardless of the situation.” Transparency, honesty, integrity, trust and respect interplay with humility to create a robust reputation for these leaders. They stand for what they believe and let people in their organizations know about it.

3. Caring Relationships and Communication

Latin American leaders believe that getting along and being close to people is a foundation for success. Related to humility, the orientation toward relationships helps to open doors to different audiences, while caring, bonding and communicating with them are crucial. They believe that working side by side with their teams and being “sleeves up” allows them to know firsthand when to intervene and support.

Many of the leaders said they have worked at different levels of their organizations and know the operation well. They have built a good perspective on how people work throughout the organizational ladder. Aware that being at the top can alienate them from the day-to-day operations, some have created personal routines to keep in touch with people across different functions and levels. Being visible across the business is a way to let people know they support and are accountable for them.

During crises, people’s well-being comes first, then come outcomes in a natural way. Working together, side by side, and consistently showing up and being present is a way for leaders to inspire. The majority of the leaders we interviewed reported that it is important to support people and let them know that they are there for them. They aim to provide a sense of comfort and protection through constant personal interactions, which is a preferred approach.

When times are difficult, leaders know they must rely far more on formal communications processes. Thus, they deliberately send personal messages to the company. Tightening relationships becomes more relevant under these circumstances. Thus, they increase the number and frequency of their communications. According to the interviewees, there is no such thing as “over-communication” in a crisis. Sending meaningful messages to reach as many people as possible is a means to increase morale as well as generate a sense of care and proximity.

Expressing feelings of empathy and concern about people’s well-being is necessary to keep their team and organization aligned and engaged. Leaders provide direction and are clear about the actions they take to make people feel supported and safe. The more specific about each step taken, the better. The reality is that, in these countries, social and political institutions often are weak and slow in responding to adversity. Corporate leaders have an opportunity to fill this void and act accordingly. To elevate spirits, precise and meaningful communications are required. This accounts for the relevance of having a sense of closeness.

Designing optimal communications and narratives requires having a pulse on individuals’ concerns and needs. Therefore, leaders actively monitor their team’s perceptions about the workforce and their feelings and worries. To complement this, they heavily rely on the information provided by institutional communications systems. In parallel, most leaders take communications and personal relationships seriously. Thus, they send personal messages to employees to reinforce the direction and provide engaging narratives. In doing so, they seek to be reliable and transparent.

I created a full line of communications for everyone to have access to procedures, systems, protocols, etc., and sent a health check to all employees through an app and had an in-house doctor and support them as needed.

Industrial Company CEO

4. Crisis as a Learning Opportunity

In this region, leaders have accepted their reality as it is: changing, unpredictable, volatile and uncertain. They stress that as their world does not function to perfection, they have built the muscle to face difficult situations as part of their business as usual. In fact, crises are considered a source of learning and innovative solutions.

When comparing themselves to their counterparts in developed countries, these leaders see themselves as fearless when facing uncertainty. They accept ambiguity and draw on their experience with past adversity to take an optimistic view toward the future. To keep up with changing circumstances, they observe what is happening inside and outside their organizations. They maintain a flexible yet open approach to this exercise, allowing them to identify the known as well as the unknown variables that are presented at any time. This capability is even more notable during a crisis. This approach has been learned through years of experience working in such contexts.

An important approach for learning while navigating turbulent waters is to enhance collaboration with key people in the business. Related to their predisposition toward developing caring relationships, it is by exploring together with their teams and stakeholders that they can create new solutions or ways of solving problems. Asking for opinions and points of view in an atmosphere of solidarity and mutual support results in favorable outcomes. By listening to and learning from others, they can create more than a brainstorming climate. They build a human connection and support network that enhances the sense of striving to succeed in the face of adversity.

We are flexible and open to risks. It is in our DNA how to manage crisis. We were born in this context and have them (crises) every other year.

Industrial Company CEO

5. Self-Confidence

In general, participants in the study displayed confidence in their capacity to solve problems and contribute to the corporate world since early on in their careers. This is underpinned by a strong drive to reach ambitious goals in their corporate careers. All of them have focused on becoming better versions of themselves. However, their sense of self-assurance

rests on two foundational experiences: education and professional experience abroad.

Together with a genuine drive to learn and strengthen their professional abilities, they have undertaken challenging assignments in their companies and pursued professional degrees in developed countries. By doing this, they sought not only to learn best practices and skills from advanced economies but also prove themselves as world-class leaders. Benchmarking themselves with peers in the academic and corporate realms has provided them with the personal belief that they are able to solve significant problems and create odds-defying solutions despite contextual adversities.

They are willing to get out of their comfort zone, both when presented with new opportunities and by actively seeking new challenges outside their current roles. Their optimistic view toward crisis comes from the fact that they have witnessed how their parents overcame obstacles. Thus, having great educational and professional experiences in developed markets has equipped them with the leadership abilities and the knowledge of processes, procedures and practices to solve problems with a better toolkit in order to make things work in their own contexts.

Work at corporations based in Europe and the USA provided them with best practices, procedures and quality standards for operating optimally. From there, these leaders created high standards of operation for their own countries. Also, they developed discipline, which they merge with their flexibility and openness to learn and think differently. In addition, Latam leaders use their positive view and emotional stability to confront crisis and make things work. They are certain that things can only improve from where they are in their local realities, as they have the capacity, know-how and confidence to get it right.

Go outside of your comfort zone, build self-confidence through international benchmarks.

Industrial Company CEO

Connecting the Dots

Our research shed light on the way Latin American leaders approach leadership during difficult times. Mainly, they leverage a sense of community, humility and caring relationships and communication to lead from the front with a decisive yet accountable approach for their companies, with a huge emphasis on caring for people. Evidence suggests that their approach to leadership is grounded in humility and a meaningful purpose of doing good for the workforce and local communities. Our findings that Latam leaders tend to be motivated by bold decision-making, purpose and caring align with findings from prior research.

Still, leaders’ self-confidence, orientation toward learning and tendency to view crises as sources of opportunity were not contemplated in past research. This key finding adds Spencer Stuart’s Learning style to the equation for understanding Latin American leaders’ mindsets and behaviors. The Learning style emphasizes exploration, open-mindedness, creativity and discovery. Besides these characteristics, leaders in this study were found not only to be avid learners, but also confident,

optimistic and able to persevere in the face of adversity.

Our study shows that it is possible for executives from other regionsto develop the leadership skills and abilities to prepare themselves to successfully perform when assigned to Latin American businesses. By developing the mindsets and behaviors that prove to be highly effective in Latam, they also prepare to excel in the VUCA world that has come to stay.

Fostering new experiences helps leaders acclimate to changing environments, a trend we expect will continue after the COVID-19 crisis. Further, by understanding the nuances of how our Culture and Individual Style Framework dimensions show up in different regions, our interventions could be better customized to specific contextual needs and challenges.

Our Methodology

We interviewed 24 world-class top leaders who were active or had recently retired (last two years) from roles

at the CEO/C-suite level. They held over 25 years of professional experience and had managed multinational large businesses (1+ annual billion USD and headcount +5000). They were born and raised in a Latin American country, and they had international exposure at the educational and/or professional levels. They had visibility, proven experience and public recognition in the regional business landscape.

First, we designed an open-ended questionnaire based on past literature review to deeply explore how Caring, Purpose, Authority, Learning and Results styles displayed in their experience as leaders. We put special focus on their description of how they coped with adverse situations that emerged in the social contexts they worked in. Interviews lasted an average of 60 minutes each and notes were taken. Then, qualitative data was processed and analyzed under the identified categories and compared to past research evidence. We aimed to describe these categories in greater detail, answering the “what” and “how” they were expressed among these executives. Finally, new categories were developed in our findings.

Interview participants by nationality

| Nationality |

Made in LATAM findings |

| Argentina |

6 |

| Brazil |

3 |

| Chile |

5 |

| Colombia |

1 |

| Mexico |

6 |

| Perú |

2 |

| Venezuela |

1 |

| Total |

24 |

Interview participants by industry and gender

| Industry |

Total |

Male |

Female |

| Conglomerate |

1 |

1 |

0 |

| Consumer |

4 |

4 |

0 |

|

Financial Services

|

2 |

1 |

1 |

| Healthcare |

4 |

2 |

2 |

| Industrual |

8 |

6 |

2 |

| Services |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| Technology |

3 |

1 |

2 |

| Total |

24 |

16 |

8 |

Interview participants by education

| Post Graduate Studies |

Made in LATAM findings |

| International Master’s Degree |

50% |

| Local Master’s Degree |

37.5% |

| No Master’s Degree |

12.5% |

| Total |

100% |

79% of sample have international experience (work and/or study).

1 Nathan Bennett and G. James Lemoine, HBR, 2014

2 Dickson, Castaño, Magomaeva, den Hartog et al. 2012

3 Dickson et al. 2012; Javidan et al. 2006

4 Gurnik 2015

5 Dickson et al. 2012

6 Ogliastri 2006

7 Davila et al. 2012; Dickson et al. 2012; Javidan et al. 2006; Ogliastri 2006

8 Dickson et al. 2012

9 Davila et al. 2012; Dickson et al. 2012; Duarte et al. 2020

10 Castaño et al. 2015

11 Gurnek 2015

12 Gurnek 2015; Javidan et al. 2006

13 Dickson et al. 2012; Javidan et al. 2006; Duarte et al. 2020

14 Gurnek 2015; Janivan et al. 2012

Interview Participants

- Rodrigo Abreu, CEO, Oi S.A.

- María Teresa Arnal, Head of Latin America, Stripe

- Iván Arriagada, President & CEO, Antofagasta Minerals

- Sofía Belmar, President & CEO, Metlife Mexico

- Florencia Davel, Latin America General Manager, Bristol-Myers Squibb

- Sylvia Escovar, President & CEO, Terpel

- Mónica Flores, President, Manpower Group Latin America

- John Graell, Executive President, Molymet, Molibdenos y Metales

- Andrés Graziosi, Global Head of Pharma Strategy & Commercial Execution, Novartis

- Sandra Guazzotti, Senior Vice President, Oracle Latin America

- Ernesto Hernández, Former President, General Motors Mexico

- Claudia Jañez, President of Specialties Division, DuPont Latin America

- Miguel Kozuszok, Executive Vice President, Unilever Latin America

- Sergio Lew, CEO, Banco Santander Argentina

- Daniel Malchuk, President of Minerals Operations Americas, BHP Group

- Roberto Martínez, President, PepsiCo Foods Mexico

- Alfredo Merino, CEO, Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma LTD

- Enrique Ostalé, Executive Vice President, UK, LATAM & Africa, Walmart

- Alfredo Pérez Gubbins, CEO, Alicorp

- Luis Rebollar, Global Business & Strategy Director, The Chemours Company

- Gastón Remy, Former Corporate Director, Vista Oil & Gas

- Denise Soares Dos Santos, CEO, Hospital Beneficencia Portuguesa

- Stelleo Tolda, President Commerce, Mercado Libre

- Fernando Zavala, CEO, Intercorp Group