CEO succession has become a hot topic and key priority for boards in India in recent years. Several homegrown corporate success stories that emerged out of India’s economic liberalization reforms, and whose leadership stability had been taken for granted, are finding themselves facing crises of succession. India’s family businesses have also, arguably for the first time, become more introspective about their future identity and leadership — especially how equipped the next generation of promoter family or professional managers is for maximizing shareholder value in the medium to long term.

A mixed track record of success in recent succession efforts begs the question — why have some Indian companies succeeded in their succession process where others have failed? And by extension, what role does the board need to play in order to enable effective CEO succession?

As leadership advisers and partners to boards on CEO selection, succession and effectiveness, Spencer Stuart spoke to several eminent industry leaders to understand their perspectives on the board’s role in succession planning. Most believe strongly that managing CEO succession is one of the most critical responsibilities of the board, and one through which they can have a direct, tangible and long-term impact on the company.

“Getting the right person as CEO is key for value creation. I feel great because, as board members, we did a great job in terms of selecting the right person, which has led to a huge impact on the shareholder value in the market.”

Harsh Mariwala

Chairman, Marico

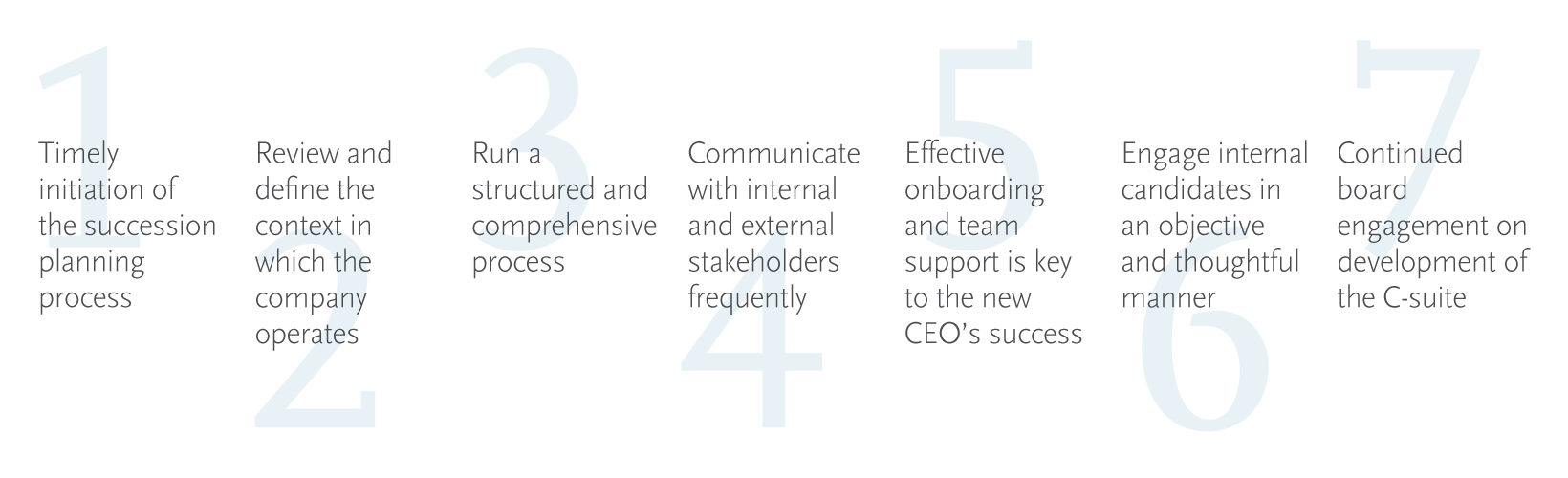

The seven critical elements of succession planning

Timely initiation of the succession planning process

In recent years, most boards in India have initiated the succession planning process in a reactive manner — when the incumbent CEO steps down or is removed or incapacitated. This emergency succession exercise often leads them to have to look outside the organization for ready-now successors, or promote someone from within the organization with serious gaps in experience or capabilities. Such situations could be prevented if boards viewed succession planning as an ongoing process consisting of annual reviews that address both short-term and long-term succession needs, including:

1. Contingency planning for scenarios involving the unexpected departure of the CEO, i.e. identifying ready-now potential candidates who could step in such situations.

2. Future planning for building the succession pipeline, which — if done regularly and rigorously — will help ensure there are ready-now candidates in place for contingency situations. Starting three to four years before the current CEO is expected to retire/depart, longer-term succession planning focuses on identifying and developing a bench of potential internal candidates, and mapping the suitable talent in the external marketplace as a benchmark. As the CEO’s term-end approaches, board discussions become more concrete and formal with specific action items.

“There may arise a situation wherein there is an instantaneous need for somebody because of a sudden departure, which leaves the board short of a reaction time. We as a company have identified people from within the organization as three sets of alternatives for this very circumstance.”

Shailesh Haribhakti

CHAIRMAN, DH CONSULTANTS

The timing of the succession process can vary depending on external developments and shareholder objectives. For example, for private equity firms, a change in senior management is usually the first item on the agenda post an investment. It is important in such situations that the PE firm make clear to the incumbent CEO/ promoter that the investment will lead to a management change.

“In private equity investment, there is a five- to seven-year horizon to implement any changes — essentially meaning that you’re looking to the exit door at the point of entry, so you need to initiate any CEO succession at the time of entry.”

Deep Mishra

FORMER MANAGING DIRECTOR, EVERSTONE CAPITAL

Review and define the context in which the company operates

Understanding the “state of play” at the time when the new CEO will step into the role is paramount. In today’s fast-paced and continually changing business environment, the context is ever evolving, making it important for the board to take this into consideration each time they discuss leadership succession. This starts by reviewing the global and local economic outlook and industry landscape. From there, the board and current CEO comprehensively define the company’s current and future strategy and culture, business opportunities and challenges, regulatory and competitive landscape, financial health, talent challenges and any other key aspects that will be critical for the new CEO to steer and navigate in the short to mid-term.

With succession processes that begin shortly before the incumbent is due to depart, the board would generally have a good idea of the context but less time to execute the actual succession. On the other hand, in cases of longer-term, planned succession, forecasting the future state and imperatives can be more challenging but is critical.

“The key attributes needed for a successor to be successful for his/her stint of five years as CEO is to have an understanding of the current phase of the economy and current phase of the industry, and knowledge of the evolution of the company. The successor needs to be ‘able and fit’ for what is required of him in a particular phase.”

Ravi Kant

FORMER VICE CHAIRMAN, TATA MOTORS

Run a structured and comprehensive process

While some Indian company boards pursue a more structured succession planning process, a majority still limit this exercise to cursory annual discussions on the topic. As best practice, chairpersons should include succession planning as part of the agenda annually, along with defining the formal process to commence once the CEO succession is formally initiated.

Formalizing the succession process consists of numerous tasks, but as mentioned earlier, at its core it requires the board to define the context in which the company is operating, and then align on the set of experiences, capabilities and values that will be key to the success of the next CEO.

In addition to identifying potential internal successors for the CEO role, it is also recommended the process include a “benchmarking” exercise at regular intervals (three to four years) to gain a more objective perspective on the incumbents and quality of CEO talent externally — particularly when the context, competitive landscape and company strategy are changing. This benchmarking exercise can also be useful for the board in creating a “wish list” of external candidates that could be considered when the actual process is triggered.

When thinking about potential external successors in particular, the board should consider not only the individuals’ capabilities relevant to the business strategy and financial operations, but also how they align with the values the company stands for and its culture.

“We start with a very big funnel of wish lists that might potentially fit for succession and over a period of time gradually sharpen that. This will lead to more formality in the process in the near term.”

Bobby Parikh

FOUNDER, BOBBY PARIKH ASSOCIATES

Further, while the nomination and remuneration committee (NRC) or, in a few cases, the selection committee (comprising select board members and external experts) are generally tasked with steering the CEO succession process, it is critical for them to brief the entire board, discuss and review progress with them at regular intervals. Not aligning the board early on can lead to undesirable delays in the succession process. On the other hand, clear, transparent communication with the board — highlighting key risks and issues and taking inputs from them — can help leverage the collective wisdom of the leaders to drive optimal and timely outcomes and manage any risks that could derail the process.

“Indian boards have to be more process led and less worried about inter-relationships.”

Naina Lal Kidwai

CHAIRMAN, ALTICO CAPITAL

Similarly, in the case of regulated entities where the regulator may have established a certain process and would need to approve the final candidate, engaging the relevant stakeholders early on and getting their view on relevant prospects is critical.

Communicate with internal and external stakeholders frequently

While the importance of timely and appropriate communication with internal and external stakeholders cannot be overstated, the frequency, content and scope of communication will vary depending on the stakeholder(s) and the stage of the succession planning process.

For instance, too much focus on succession when a new CEO has just taken over could have the unintended consequence of creating uncertainty in the senior management and insecurity for the CEO. At this point, discussions should be more focused on development of the CXO pipeline rather than imminent succession.

On the other hand, if a transition is imminent, the board should themselves engage a wider set of external stakeholders — investors, regulators and media. Proactively communicating and controlling the messages — both internally and externally — rather than being reactive or non-communicative is important to avoid speculation. This often involves the board walking a tightrope to effectively balance transparency with maintaining the confidentiality that is equally key to the process.

Effective onboarding and team support is key to the new CEO’s success

The succession process does not end with the placement of the new CEO. It should include planning for effective onboarding, with the board playing a big role in supporting and guiding the leader towards ensuring smooth induction and transition.

In founder-driven organizations, succession and transition planning should also include formal agreement and documentation of the roles of the outgoing promoter-CEO (who often becomes the chairperson) and the new CEO. While many chairpersons and their professional CEOs maintain healthy working relationships, upfront discussion and formalization of roles, responsibilities and decision jurisdictions can help foresee and address any aspects that can lead to the breakdown of the relationship and impact the company as a whole.

“You need to structure how the CEO and non-executive chairperson will address critical issues and resolve conflicts. More than just the written role descriptions, you (as the chairperson) need clarity of mind — to give the CEO his space to operate and step away from issues that fall within his purview.”

Harsh Mariwala

Chairman, Marico

Engage internal candidates in an objective and thoughtful manner

The reality of any CEO succession process is that there can only be one CEO. The eventual selection of one of many internal aspirants or an external candidate is bound to create some disappointment among the other internal contenders. The shifting internal power dynamics can lead to the departure of key senior executives — many of whom have a key role to play in the current or future success of the company. The board can help minimize such “collateral damage” by running a process that is honest, transparent and is seen to be fair and robust by candidates. Internal candidates should be given a fair chance to be objectively evaluated for the role. Engagement of external leadership assessment experts could enable objective evaluation of internal as well as external candidates — and reduce the impact of internal perceptions about the fairness of the process. Clear, continual communication, trust building and mentoring are key to building trust with internal candidates. It is important that they receive the right kind of advice from board members who they trust. Having a feedback loop in these situations is important for the internal candidates who do not get the top role.

“In almost any succession, whether involving an internal or external candidate, it always tends to result in collateral damage — and this can be reasonably anticipated. There are ways to mitigate the collateral damage wherever necessary, as well as being honest and upfront about letting someone go is always helpful.”

Arun Adhikari

CHAIRMAN, NIELSEN INDIA

The board should think through various scenarios, including evaluating the organizational structure and changing it if required to retain key talent and support the CEO for long-term success in his/her role. It should also lay special emphasis on structuring and articulating the internal communication, so that the senior management as well as other employees feel appreciated and are comfortable with the final outcome.

“In taking in an external CEO, a detailed analysis of the pros and cons of both the internal and external candidates took place before a decision was made about proceeding with an external candidate. This detailed analysis is instrumental in the process being transparent and clear to all.”

Naina Lal Kidwai

CHAIRMAN, ALTICO CAPITAL

Continued board engagement on development of the C-suite

Leadership succession discussions should go beyond the CEO position to cover the CEO’s direct reports as well as emerging high-potential executives. When directors invest time and effort in reviewing performance, assessing and developing key C-suite executives on an ongoing basis, not only will the company have a stronger bench of talent for any planned or unplanned succession, but it can enable the board to foresee and address any key talent risks in a timely manner.

Overall, the succession process should not be limited to building a list of viable backups for the CEO but be part of a holistic leadership development approach, which could include mentoring of key talent by board members, purposeful job rotation, and assessment, coaching and development for high potential future leaders. Having an annual review of the leadership pipeline and discussion on how to enable their development is an absolute must.

“We need to concentrate on creating a culture of institutionalized management development through all levels so it comes through to the value system of the organization. Creating a culture we are proud of and passionate about will increase the possibility of internal candidates suitable for succession.”

Asanka Rodrigo

PARTNER, HEAD SOUTH ASIA, PRIVATE EQUITY AT ACTIS ADVISERS

Common hurdles — Avoiding the pitfalls

Clearly, industry leaders’ perspectives about what constitutes a good succession process seem to align. However, the very public succession failures at some of India’s most respected companies indicate that there are some real challenges to getting succession planning right.

Low comfort with candid feedback in the Indian corporate culture

Many directors who have served on both international and Indian boards observe that when compared to company and board cultures in the West, Indian culture and executives tend to be less comfortable with direct feedback, with the senior management also often being less receptive to criticism. Indian societal norms and the perception of the Indian corporate world as “cliquish” at senior levels sometimes lead directors to avoid being seen as disagreeable by their peers — especially those with whom they may also have social or external professional relationships.

This dynamic between the board and senior management is understandably counter-productive as it may delay or altogether preclude necessary course correction when the performance of the CEO falters. In such an untenable situation, it becomes imperative that the board gives direct feedback to the CEO or take a strong stance with the CEO, if required, to live up to its fiduciary responsibility. The independent chairperson (where there is one), lead independent director or group of independent directors, in particular, need to ensure that such feedback discussions take place in a timely and appropriate manner.

“In India, we are far too nice in our boards as well as over-friendly. We don’t object to the CEO or the chairman of the board even if there’s an issue of accountability or some issues that require sorting through. Ideally a board should be constructive bearing in mind the right thing for the company and its stakeholders — even if this goes against the wishes of the CEO or chair.”

Naina Lal Kidwai

CHAIRMAN, ALTICO CAPITAL

Promoters procrastinate discussion on succession

Founder leaders and professional CEOs can often find it hard to acknowledge the idea of their ageing/mortality or recognize how another leader could be more suitable for the role of CEO as business context changes. Therefore the onus is on the board and NRC to ensure that succession planning is not overlooked. Putting in place a process for the identification and development of internal successors as a critical key result area (KRA) for the CEO and other CXOs, and reviewing their performance on this annually can help keep them on track.

“CEOs don’t like discussions on succession — they end up thinking they are immortal and are going to live forever.”

Ashok Chawla

FORMER CHAIRMAN, NATIONAL STOCK EXCHANGE OF INDIA

Company succession is confused with family succession

Societal norms often lead to the expectation, even from promoters of large corporates, that the mantle of the CEO will pass from one generation to the other. This expectation at times may overlook on-the-ground realities, such as a next generation of the promoter family not being interested in being part of the family business or best suited to take on the role. In this scenario, an assertive board that is able to give its views to the promoter directly can help alleviate the problem. The promoter needs to keep his/her eye on the bigger picture and focus on doing what’s best for the company; the board’s role is to provide the counsel and assertiveness to keep the decisions of the family anchored to the long-term health of the business.

Conclusion

Managing a CEO succession planning exercise presents a number of challenges and complexities. A successful outcome is when the new CEO not only has a positive impact on the financial performance, but also on the culture, people and values of the company, and is surrounded by a capable and aligned senior management team. A well-run succession process is key to the long-term sustainability and growth of any company.

The board of directors, as fiduciaries of company stakeholders, must own and drive the succession process. Embracing the critical elements of a timely, structured and thoughtful process and avoiding the pitfalls improve the probability of a successful outcome.

Corporate governance in India is seeing winds of change blowing in the right direction, and in the coming years, more boards will oversee enlightened and effective succession processes that produce exceptional CEOs and senior management teams.